Fenner Watershed

Fenner Watershed

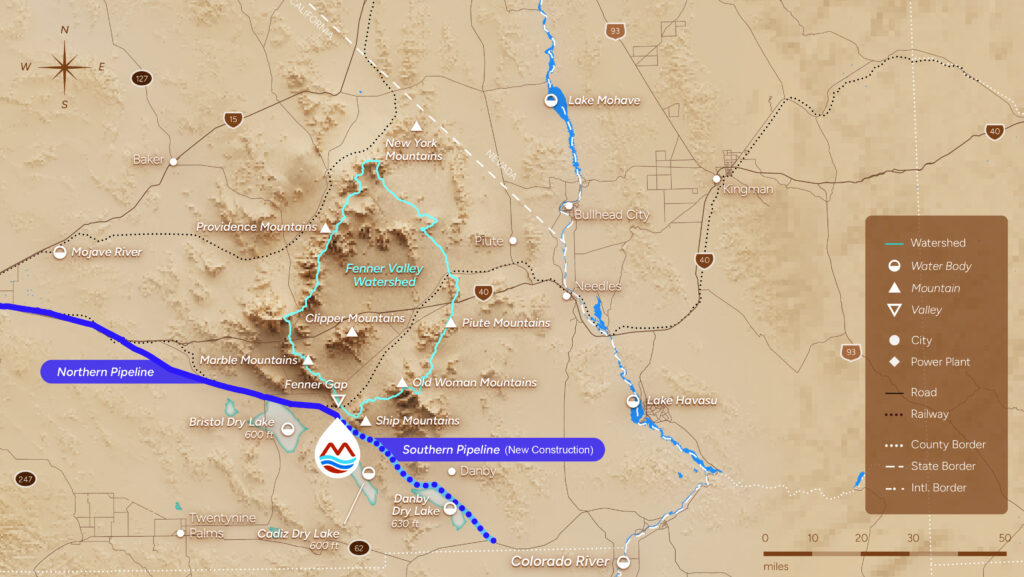

In the sunbaked Mojave lies a resource as vast as it is vital – the Fenner Watershed. Covering approximately 1,300 square miles, it has quietly stored water underground for centuries, fed by rain and snowfall in its surrounding mountain ranges that rise to more than 7,500 feet in elevation.

The Fenner Watershed is part of a broader closed basin made up of the Fenner, Bristol, Cadiz Watersheds to the south totaling 2,700 square miles. Groundwater beneath these watersheds slowly flows underground toward a shared natural outlet at the lowest point in the watershed – the Bristol and Cadiz Dry Lakes – where water turns to brine and is ultimately lost to evaporation.

The Mojave Groundwater Bank sits at the base of the Fenner Watershed in the Cadiz and Fenner Valleys.

Without active management, fresh water able to support communities and drought resilience is lost.

A Water Resource Larger Than Lake Mead

The Mojave Groundwater Bank watershed is located less than 100 miles to the southwest of Lake Mead.

How Water Moves Through the System

Natural Recharge

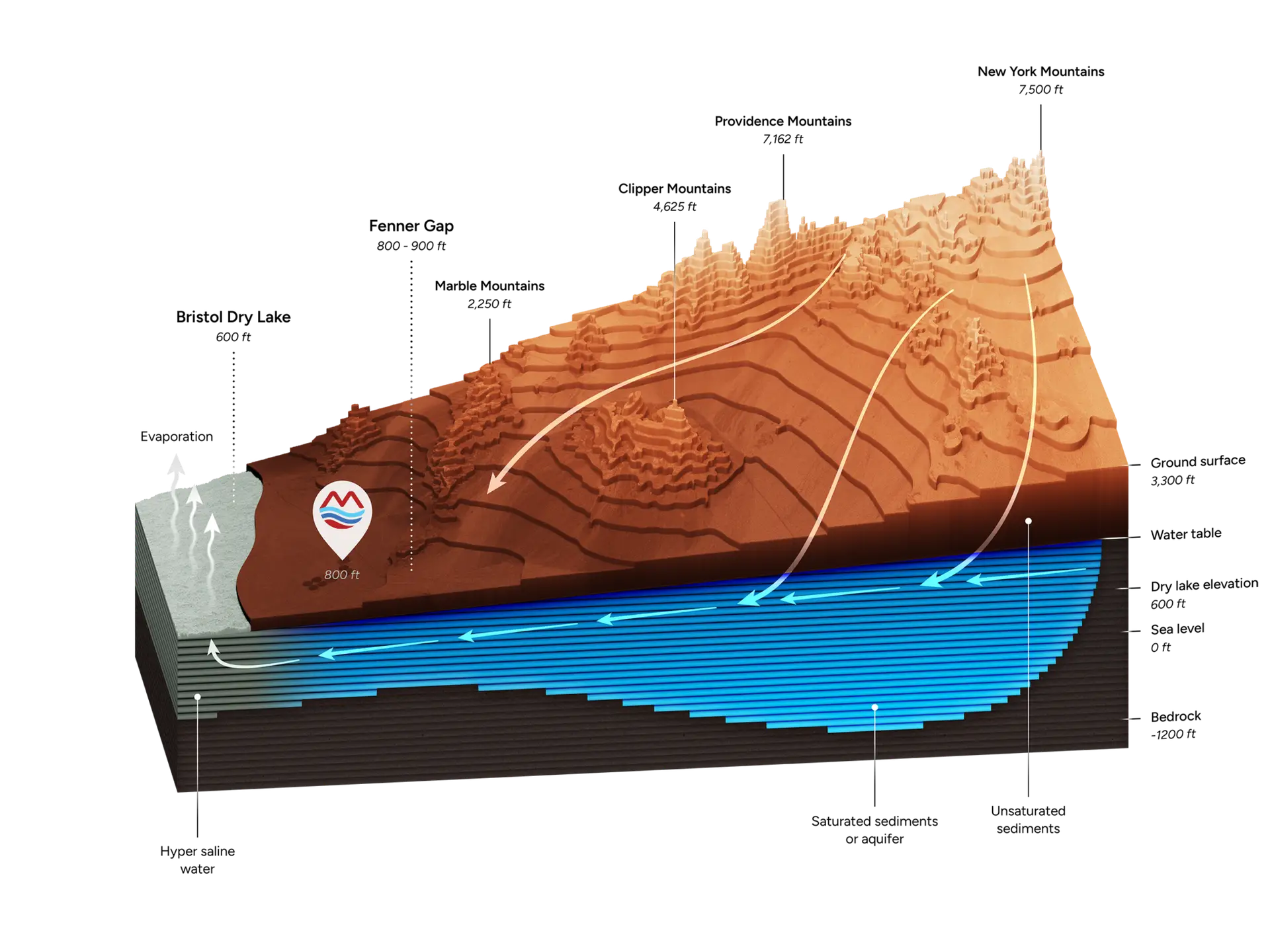

Groundwater in the aquifer system is naturally replenished through two primary processes:

- Infiltration of rain and snow into fractured bedrock exposed the surrounding mountains; and

- Infiltration of ephemeral stream flow in sand-bottomed washes in the Valleys

Precipitation in the Fenner Watershed is much more significant than other desert watersheds because the surrounding mountains such as the NY Mountains, which reach approximately 7,500 ft elevation, are not in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and receive over 10” of rain per year and significant snowpack during winter storms.

Experts at CH2M (now Jacobs ) used site-specific data and the 2008 U.S. Geological Survey INFIL3.0 model to estimate the natural recharge to the MGB project area at the Fenner & Cadiz Valleys to be approximately 32,000 acre-feet per year.

Evaporation at the Dry Lakes

Water that is not captured at the MGB project area will continue by gravity flow to the Bristol and Cadiz Dry Lakes – the lowest points of the closed basin. At the Dry Lakes fresh groundwater mixes with the highly saline groundwater zone beneath the lakebeds and becomes trapped in the salt sink, and is no longer fresh or available to support residential or community water uses.

Groundwater beneath the surface of the Dry Lakes has salinity levels ten times higher than that of the Pacific Ocean. This saline groundwater is drawn upward by hot, dry desert conditions and evaporates, leaving behind thick salt deposits – primarily calcium chloride, sodium chloride and brine-saturated sediments. Elevated calcium chloride levels in the soil contribute to a bound, puffy surface that limits dust emissions as the surface dewaters.

Studies conducted by the Desert Research Institute estimate that approximately 31,250 acre-feet of water evaporate annually from these dry lake surfaces—demonstrating that water entering the system is eventually lost.

Why Groundwater Management Matters

In a region where every drop matters, the Mojave Groundwater Bank exists to manage this natural loss. By capturing and storing water before it reaches the dry lakes, the project helps preserve a resource that would otherwise evaporate.

This approach combines conservation, active recharge, and smart water banking with extensive scientific monitoring to ensure long-term sustainability and protection of the surrounding desert ecosystem.

Why Groundwater Management Matters

Science, Oversight, and Accountability

All operations of the Mojave Groundwater Bank are governed by a Groundwater Management, Monitoring, and Mitigation Plan (GM3P), approved and enforced by San Bernadino County. This plan establishes one of the most extensive pre-operational monitoring protocol ever established for a groundwater system.

More than 100 monitoring elements track groundwater levels, water quality, land subsidence, air quality, and natural springs throughout the life of the project. For every critical resource, the GM3P establishes pre-planned adjustments to avoid adverse impacts to the surrounding environment. Monitoring data is publicly available and reviewed by an independent Technical Review Panel to ensure transparency, accountability, and environmental protection.

Access the Groundwater Management, Monitoring, and Mitigation Plan here.

Protecting the Environment

To learn more about the projects dedication to protecting the surrounding environment, visit Studies & Technical Reports